Poland’s Rise As A Pioneer In Modern Football Stadiums

- Facts & Figures, StadiumADS

- Read Time: 7 min

Already nearly 9 billion Zloty (2 billion Euro) have been spent by Polish taxpayers on modern football stadiums. By 2028 this sum could significantly exceed 10 billion. By then, the country is expected to have 35 stadiums that meet the highest requirements. The infrastructural transformation is ongoing, but already Poland has gone from being a periphery to becoming a basin of modern football arenas.

Many fans surely remember where they were at the moment when Michel Platini in Cardiff took out a card with the words “Poland and Ukraine.” It was April 18, 2007 when the two countries were announced as the hosts for the UEFA EURO 2012.

Candidacy was, after all, Ukraine’s idea. They were the ones with strong clubs, influence in UEFA and three of the four stadiums (Shakhtar was building, Kharkiv and Kiev needed upgrading). In Poland, there were single stands in Krakow or Poznan and a modern – at the time – gem in Kielce, too small and too far from any airport to be considered.

And yet it succeeded ...

Today Poland has 28 modern stadiums, next year there will be 31, and by 2028 there may be 35. Considering smaller stadiums, those for athletics or speedway, we would talk about over 100 investments to sports stadium constructions. A boon for the construction industry, but also new opportunities for sports clubs in the areas of hospitality and digital stadium marketing.

The Polish stadium boom is usually associated with the organization of the 2012 European Championships. Not without reason – this was a great catalyst. As in the case of Germany and the effect of hosting the 2006 World Cup, the flagship projects sharply raised the standard and caused other sports clubs and cities to follow suit, creating a ripple effect of new investments. In Poland, this effect was even stronger than in Germany, as the starting ceiling was much lower, and the already clear economic development was accelerated by entry into the European Union. Even before accession, however, the country’s development indicated that there would be plenty to build with.

Poznań is a perfect example: only between 2000 and 2007 did the city’s budget income almost double (an 83 percent increase). This allowed for the development of plans that changed as financial opportunities grew. At first, the city only wanted to close the body of the stadium and roof a set of stands. Later, a decision was made to remove the old embankments and build new stands.

Cities bear the greatest burden of modern football stadium construction

It is from the budgets of cities that the vast majority of the money for which stadiums are built in Poland comes. Those built solely with government money are a rarity; of the 27 large stadiums, only the PGE Narodowy was built this way. Poles also do not build with money directly from EU funds – only three significant stadiums are investments of this type – these are Białystok, Lublin and Ostróda.

Private money doesn’t like Polish stadiums for a simple reason: either the return on investment is very low, or you have to add more. To date, not a single stadium has been built in a public-private partnership (PPP) either. The Polish sports and entertainment market has been too small for private investors not to lose out. Perhaps the ice will be broken by the planned PPP for Polonia Warszawa’s stadium, whose numerous additional functions and location in downtown Warsaw promise success.

In contrast, completely private stadiums remain the domain of wealthy soccer enthusiasts who do not count on a return on investment – like the Witkowski family in Nieciecza. They are the only ones in the 21st century who have built a stadium meeting the highest requirements quite for their own money.

Cities bear the greatest burden of stadium construction

It is from the budgets of cities that the vast majority of the money for which stadiums are built in Poland comes. Those built solely with government money are a rarity; of the 27 large stadiums, only the PGE Narodowy was built this way. Poles also do not build with money directly from EU funds – only three significant stadiums are investments of this type – these are Białystok, Lublin and Ostróda.

Private money doesn’t like Polish stadiums for a simple reason: either the return on investment is very low, or you have to add more. To date, not a single stadium has been built in a public-private partnership (PPP) either. The Polish sports and entertainment market has been too small for private investors not to lose out. Perhaps the ice will be broken by the planned PPP for Polonia Warszawa’s stadium, whose numerous additional functions and location in downtown Warsaw promise success.

In contrast, completely private stadiums remain the domain of wealthy soccer enthusiasts who do not count on a return on investment – like the Witkowski family in Nieciecza. They are the only ones in the 21st century who have built a stadium meeting the highest requirements quite for their own money.

Investments for another billion in the queue

The already mentioned stadium for Polonia Warsaw (16,000 seats) is the largest pending investment. The costs, estimated at 500 million Zloty, are due not so much to the scale of the stadium, but to the packaging of the project which also includes an indoor basketball arena (1,200 seats).

Second in line is Ruch Chorzów stadium (16,000 seats), which – after years of neglect – has become more than 100 percent more expensive than estimates from a decade ago. These are the effects of inflation in the first place, which the Chorzow local government would not have been able to bear on its own. Before the elections, however, the outgoing government pledged to cover half of the construction costs, and now the 249-million stadium has a very real chance of being built in 2027.

Much smaller will be the modern football stadiums in Rzeszow (Resovia) and Czestochowa, where further reconstruction of the Rakow arena is planned. In both cases the goal is a capacity of about 8,000 seats. In Częstochowa, new western and northern stands are planned, while in Rzeszów a completely new arena will be built – the tender has just been awarded.

What have the new stadiums given Poland?

Quite a lot. Poland‘s soccer league is rapidly growing and the average attendance (despite the recent pandemic) has managed to expand to unprecedented proportions. Ekstraklasa matches are attended by an average of nearly 12,000 spectators – more than twice as many as 20 years ago. In tandem with this, the budgets of clubs and the value of broadcasting rights are swelling.

Audience demographics are also changing; better stadiums have made it possible not only to encourage families with children, but have also opened the door wide for fans with disabilities. These responded with enthusiasm, and today Poland has one of the most active communities of disabled fans in Europe, from which others are following the example.

Modern football stadiums have also become a solid tool for promoting Poland, which has already hosted two Europa League finals since Euro 2012, the UEFA Super Cup will be held at PGE Narodowy in 2024, and the Conference League final will be held at Tarczynski Arena a year later. Stadiums on the Vistula River also hosted the U21 Euros in 2017, the U19 World Cup two years later, and in 2025 the Euros will come again, this time the women’s U19s. And it’s important to remember that sporting events are just part of a rapidly growing sector of events in which Poland has more and more to offer, not just to domestic audiences.

-

written by Paul Mayer

How Football Clubs Optimise Their Stadium Marketing in 4 Steps | 2025 Guide

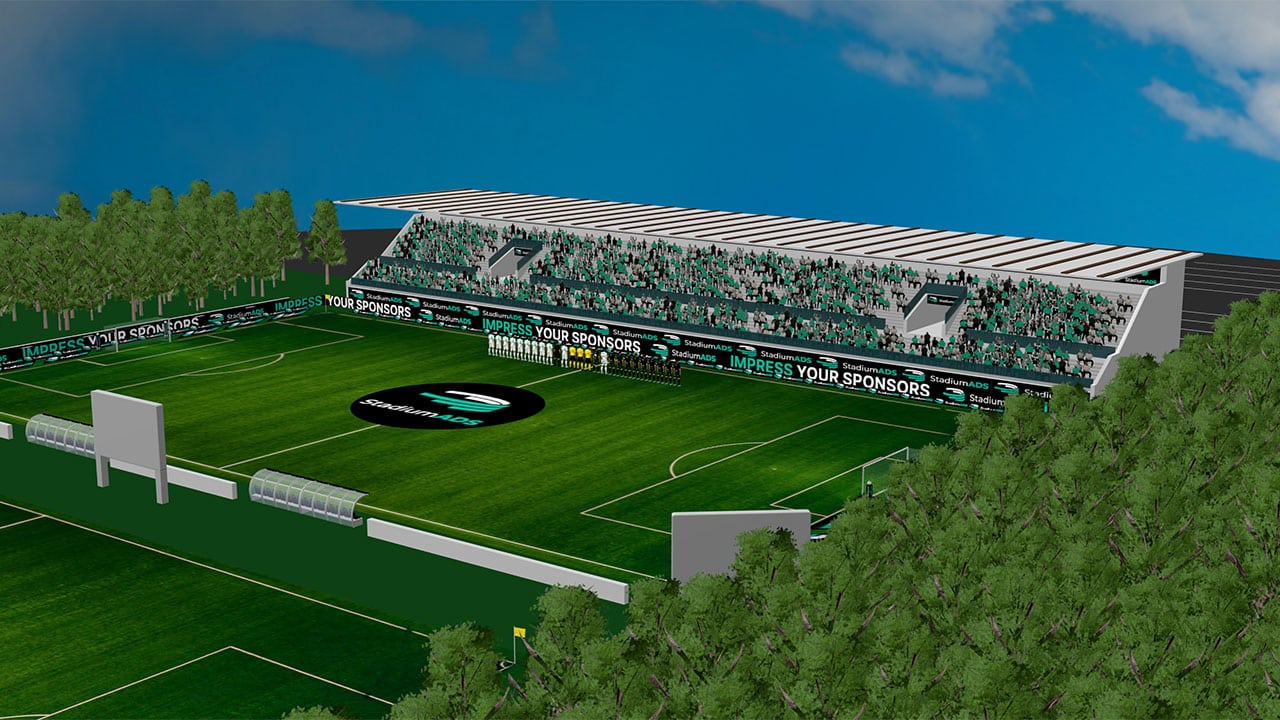

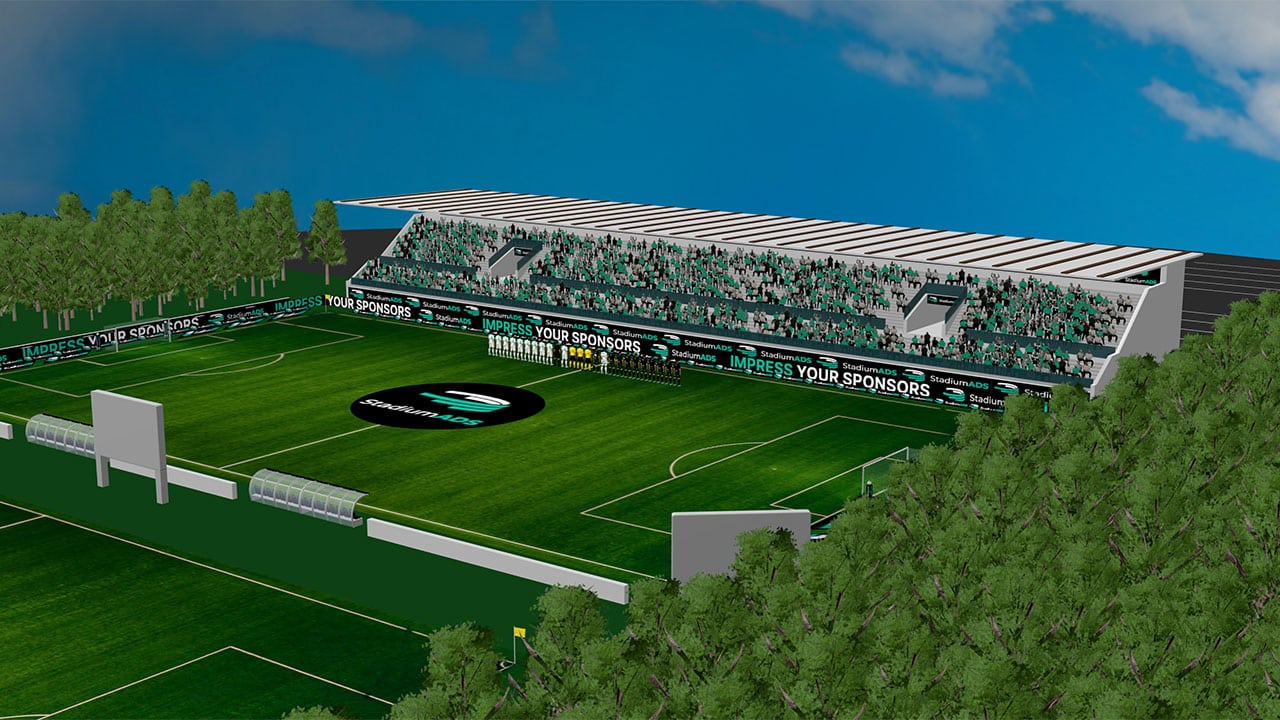

With the help of StadiumADS the Allianz Stadion of Austrian club SK Rapid was recreated as a detailed 3D model in 4 steps to authentically enhance pitch decks and save sales staff valuable working time.

Stadiums Football Clubs can choose from in 2025

In this post you’ll get a detailed overview to decide if StadiumADS is the ideal solution for you and your team for better marketing.

SK Rapid, Vienna Vikings & Danube Dragons rely on StadiumADS

Three Austrian top clubs will utilize StadiumADS to enhance the marketing of their advertising spaces in stadiums, on jerseys, and in media areas.

How Football Clubs Optimise Their Stadium Marketing in 4 Steps | 2025 Guide

With the help of StadiumADS the Allianz Stadion of Austrian club SK Rapid was recreated as a detailed 3D model in 4 steps to authentically enhance pitch decks and save sales staff valuable working time.

Stadiums Football Clubs can choose from in 2025

In this post you’ll get a detailed overview to decide if StadiumADS is the ideal solution for you and your team for better marketing.